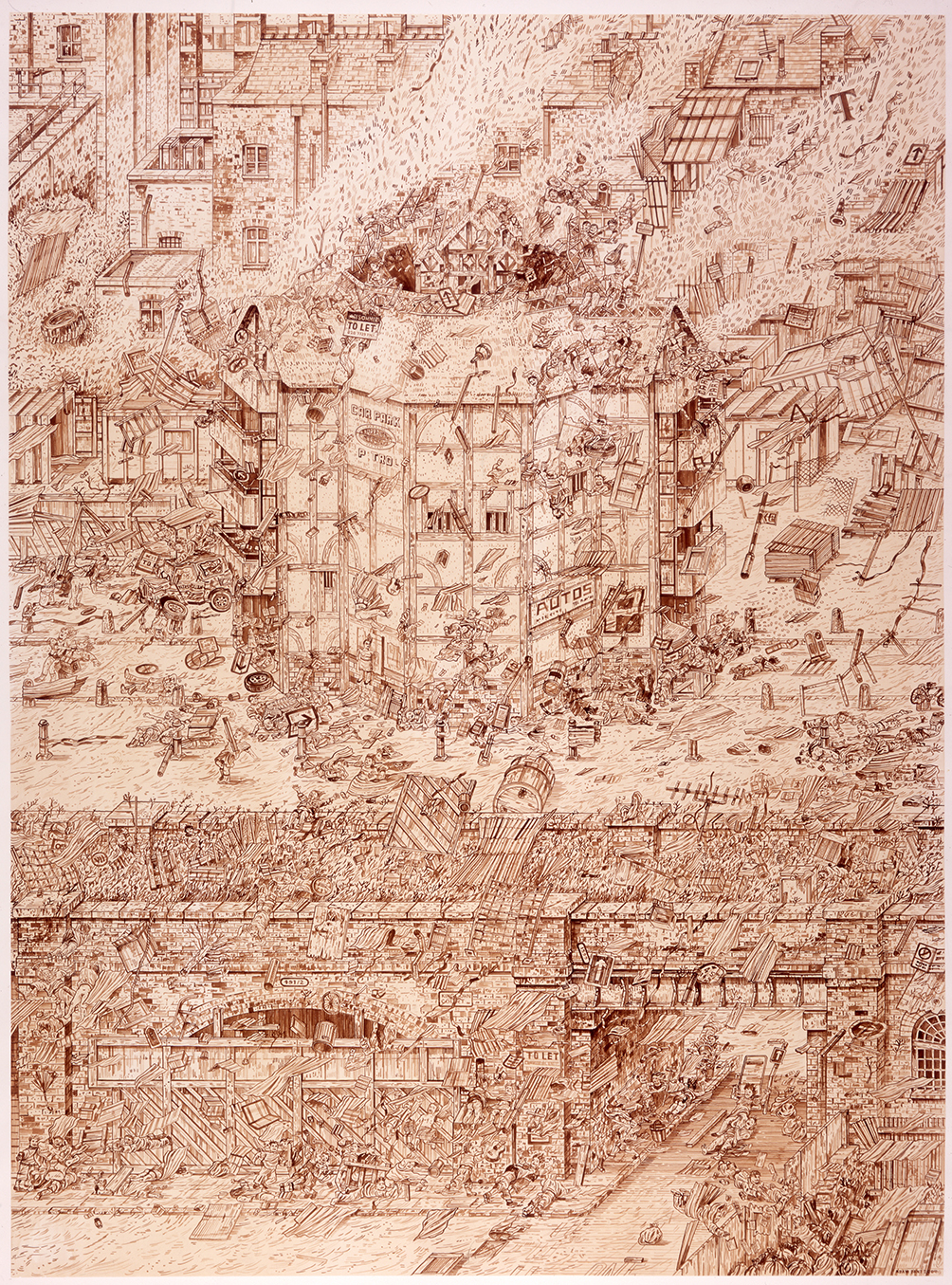

Adam Dant is a Shoreditch-based cartographer, whose narrative ink drawings depict London’s East End in myriad beguiling ways. We talk to him about his latest exhibition:

What can you tell us about your exhibition at Rich Mix, Bethnal Green: A Journey to the Heart of East London?

A Journey to the Heart of East London is a cartographic display on the mezzanine floor of Rich Mix, showcasing greatly enlarged maps from my new book, Adam Dant’s Maps of London and Beyond.

This scaling up is the reverse of how I usually work cartographically. Typically, I’ll create the original drawings on big sheets of paper taped to the studio wall, before reducing them in size to appear as lithographs, woodcuts or in the pages of an atlas. The viewer’s experience at Rich Mix is almost like being inside the atlas itself.

Your maps focus on various, wide-reaching topics, from the dreams of London’s East End inhabitants to 2000 years of the capital’s riots. How do you decide upon and research these themes?

When you think of what an artist does, you don’t usually imagine someone sitting in a library sifting through piles of old phone books... but that’s a large part of what I do.

I live immediately next to the City of London. Its 2000-year history has provided me with themes for lots of my maps and books. Maps of the city’s coffee houses, lost streets, imaginary libraries and nude statues have all been born from my wanderings around the square mile and fraternising with the various types of people who live and work there.

What first ignited your interest in cartography?

When I was about 6-years old, I bought a guidebook on the ruins of Pompeii from a school jumble sale. It had a fold out map in the back, and as the only other maps I knew were from the novel Treasure Island, I figured that this must also be a treasure map.

I drew locations of buried treasure all over this map of Pompeii alongside gangs of marauding cowboys and musketeers. I showed this illustrated map to my school pal Tullio Martinelli. It was a Catholic school and lots of the children were from Italian families. Tullio, with his nascent but scanty knowledge of ancient history, came to the conclusion that I was involved in an act of cultural appropriation and launched into a petulant tirade screaming: “This belongs to me, this is Pompeii, this is Italia!” After the resulting scrap, the map was even more tatty than before.

I still have this map, and took it with me when I visited Pompeii as a scholar in printmaking at The British School in Rome. Sadly, it wasn’t possible to dig for treasure at the place I’d marked with an X, not without being carted off by the carabinieri, anyway.

Later that day after visiting Pompeii I was sitting on the terrace of a cafe in Naples, when I looked over to the table next to me. A girl was writing in her notebook, with a brown leather satchel open on a chair. I read the name that was written on the satchel’s inside flap: Tullio Martinelli, St Laurence’s RC Primary School, Cambridge. The girl was a Classics undergraduate and had bought the satchel from a second-hand shop. I thought it was Tullio coming after his map again!

How did you come to focus on the East End?

I moved to Redchurch St, E1 in around 1993, as all the lithographers, typesetters, plate makers, foil blockers were there; everything I needed to make my prints.

I thought it would be a nice idea to create a map of my immediate neighbourhood, Shoreditch, on a different theme every year. Along with lots of the locals who used to drink in The Owl and Pussycat pub, we fostered an interest in the history of Shoreditch, its Elizabethan theatre scene, industrial heritage, grand mansions and notable locals.

The focus on my own neighbourhood as the subject of my maps consciously bears out perennial clichés as to artists finding the subjects for their work on their own doorstep. Unwittingly I have allowed Redchurch Street to become my Cookham!

How long might it take you to finish a map?

Lots of my maps are half forged from nosing around in archives and libraries and half from drawing in the studio. They are also the result of lots of conversations with various people, from which I’ll usually end up with a list of stuff that needs to go in it, and then, when the list is all crossed, off the map is finished.

You featured in a Guardian article recently about your Club Row studio being threatened with closure. What are your thoughts on artists’ studio spaces in London?

Shoreditch might not appear to be the grubby neighbourhood sympathetic to the vague needs of the artist that it used to be, but then, it never was intended as an artistic enclave.

The contingencies that impinge on or condition how an artist works in this neighbourhood now are still just contingencies, the same as in the late 1980s.

Just replace ‘derelict loft in gloomy, abandoned, ex-industrial backstreet’ for ‘overpriced, low-ceilinged, cheap plasterboard-clad rabbit hutch’, and you’ll find an artist can make art in both.

What are the main difficulties for artists these days, and yet why is art so important?

Art is important because it creates problems where there were none and attempts to solve them. Anyone who can engage with the world in such a fashion is engaged in seeing it anew, in premising the preposterous and in getting up peoples’ beaks, all of which is important to mess with the status quo.

I like what Dinos Chapman wrote on one of the Chapman Brothers’ early drawings: “Your expectations of culture are tragic!” It made me realise that people who ‘get’ what you’re doing as an artist are usually few and far between. Instead, as an artist there is an emphasis on needing to create widespread appeal, for example by repeating your same message over and over again. This can be unfulfilling and stifling, so it’s better to plough ones own furrow.

What would you say to young artists hoping to pursue a career in the arts today?

Don't be afraid of the dirty words 'craft', 'form' and 'tradition'. Realising works of art completely within their own terms of reference is an important exercise, please don't refer to a painting, print, drawing or sculpture as a 'piece'.

What made you decide to join the Artimage collection?

Working with Artimage means being in good company. Not only that, but they also make my work available for wider use.

You can buy copies of Adam Dant’s book: Adam Dant’s Maps of London and Beyond, here.

View our full Adam Dant collection, or browse a curated selection of images below:

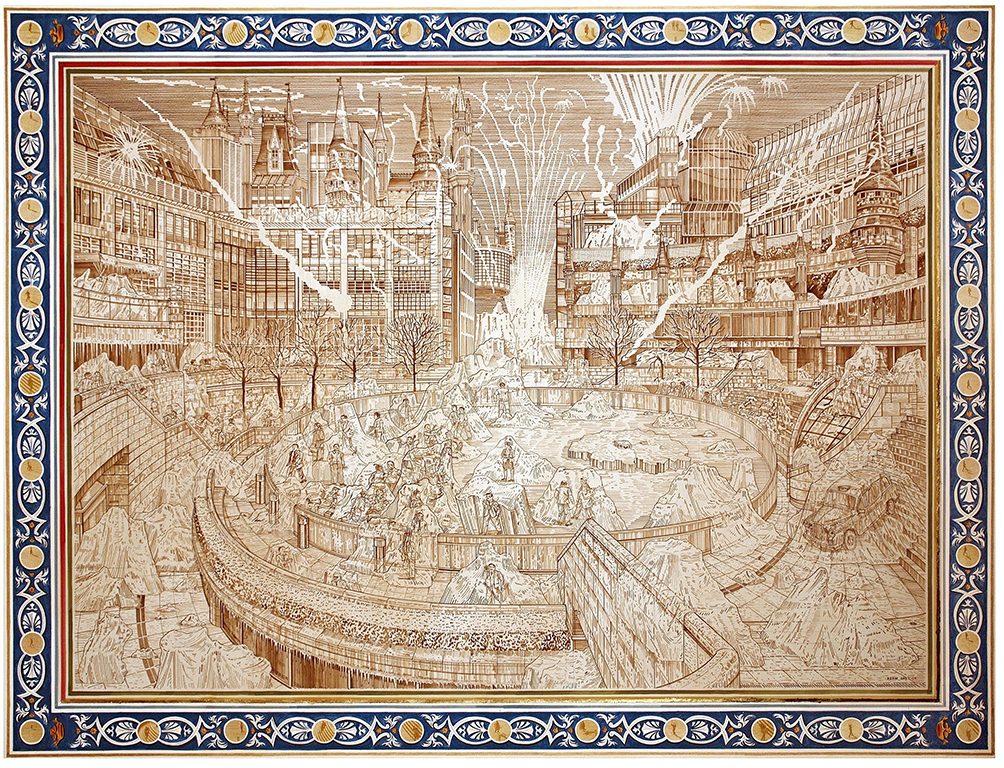

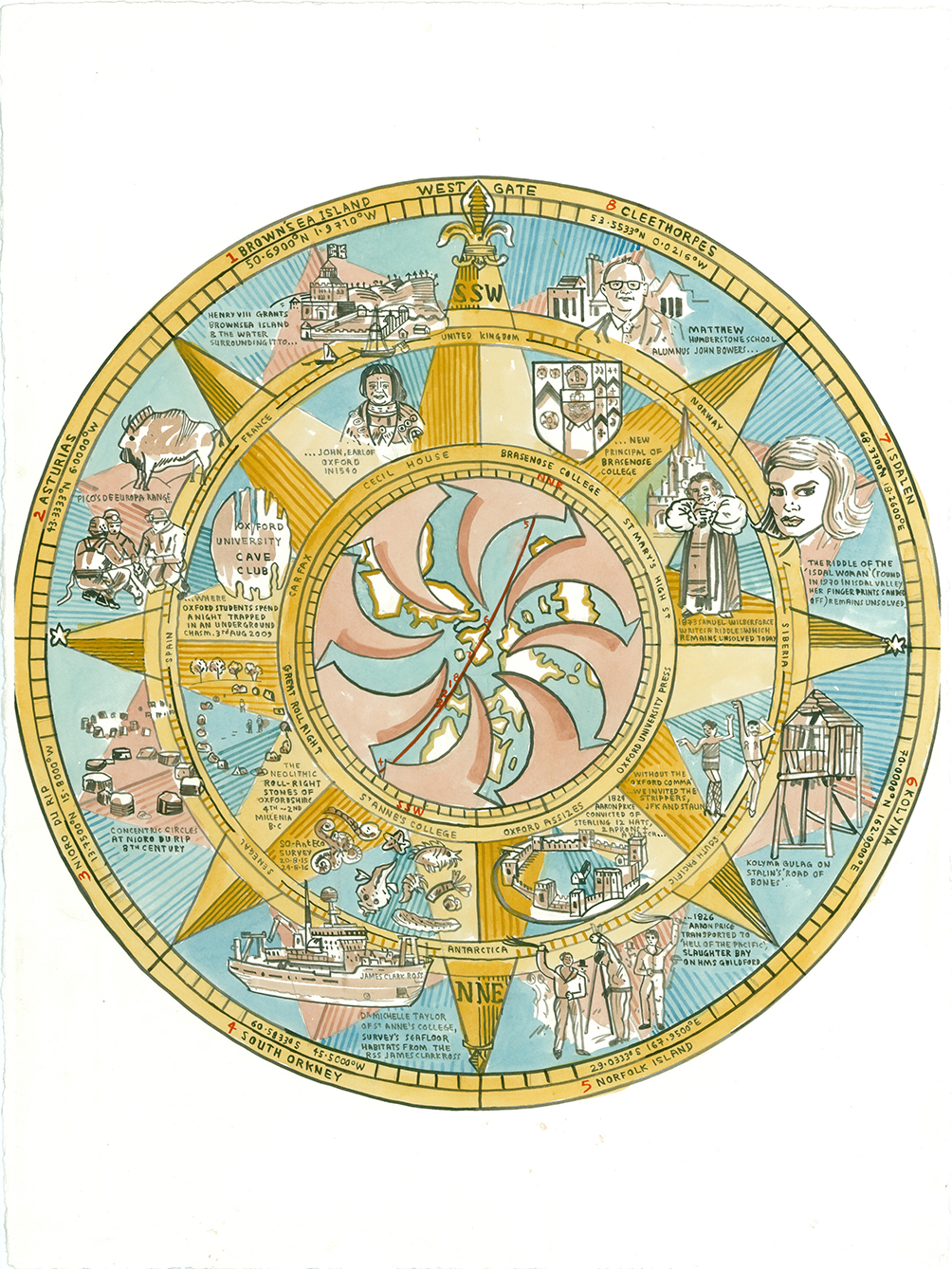

The Westgate Meridian, Oxford, NE-SW, 2016

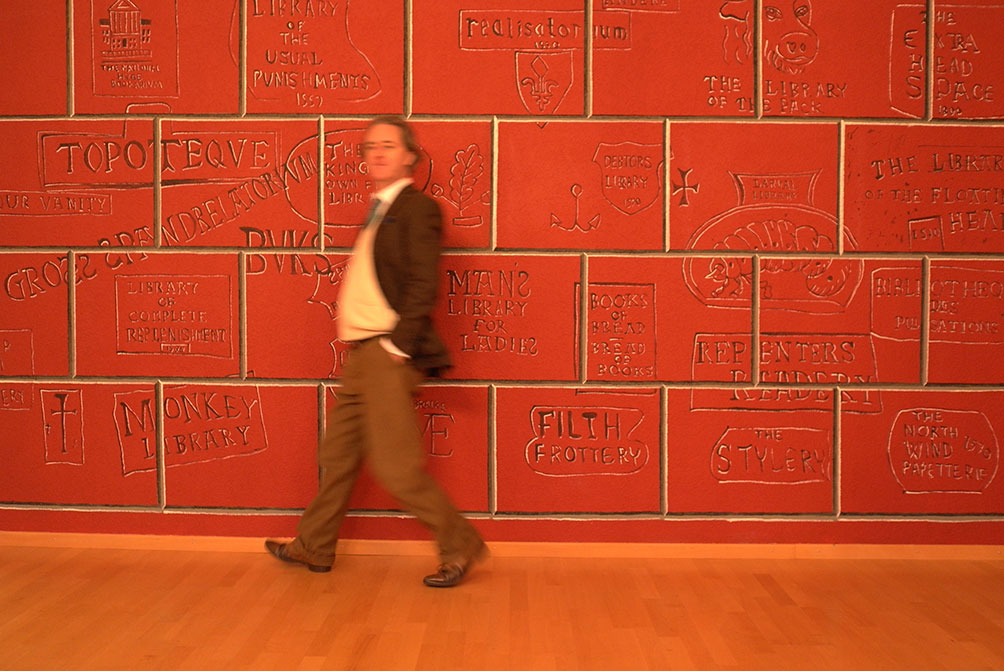

Budge Row Bibliotheque, 2015 (Installation shot)

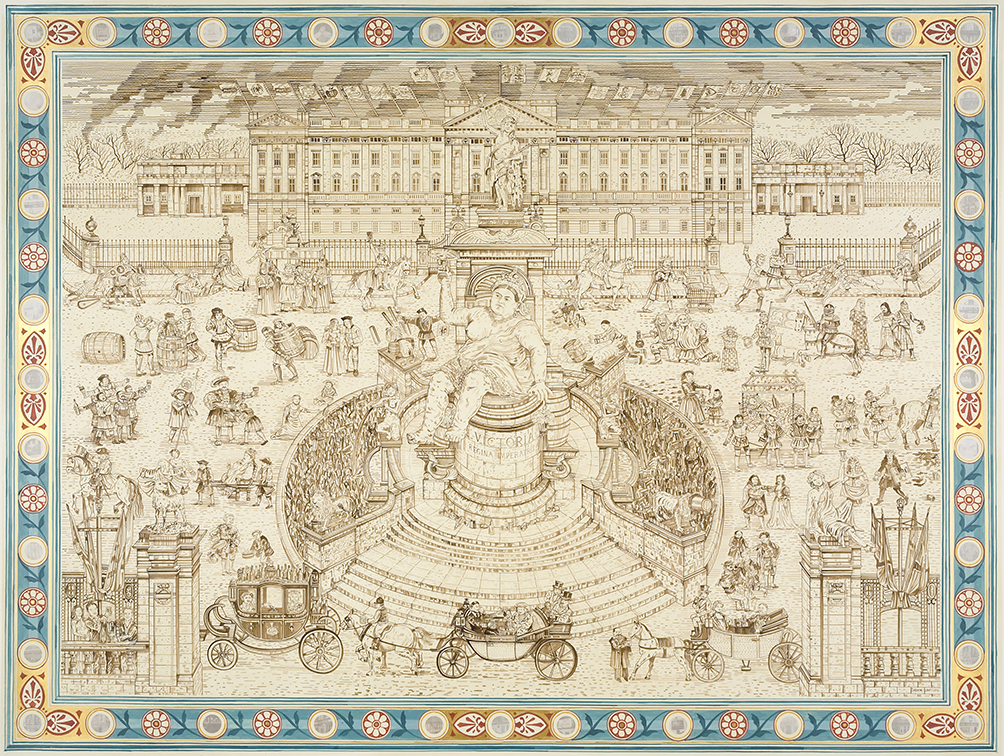

Royal Drinking, 2010

Shakespeare's Shoreditch, 2016

How to license an image

To request an image, log in or register for an account.

Need help? Contact our team for expert guidance on finding the right image for your project. Email [email protected] or call +44 (0) 20 7780 7550.

Related pages

- Browse our Adam Dant collection

- How Artimage works

- Sign up for our monthly newsletter full of art news, artist interviews and new images.

Images: Industrial Shoreditch, 2015 © Adam Dant. All Rights Reserved, DACS/Artimage 2018; Broadgate Ice rink, 2011 © Adam Dant. All Rights Reserved, DACS/Artimage 2018; Treasures of Hackney, 2014 © Adam Dant. All Rights Reserved, DACS/Artimage 2018; Bibliopolis, 2015 (Installation shot); The Westgate Meridian, Oxford, NE-SW, 2016 © Adam Dant. All Rights Reserved, DACS/Artimage 2018; Budge Row Bibliotheque, 2015 (Installation shot) © Adam Dant. All Rights Reserved, DACS/Artimage 2018. Image courtesy Bloomberg Gallery; Royal Drinking, 2010 © Adam Dant. All Rights Reserved, DACS/Artimage 2018; Shakespeare's Shoreditch, 2016 © Adam Dant. All Rights Reserved, DACS/Artimage 2018.